I was strangely troubled recently to hear a bright, idealistic, youngish person whom I like a lot (Ivy undergrad, professional degree candidate) worry aloud frowning anxiously (seriously), “I am passionate about what I am researching; I just hope I will be able to get a JOB when I get done with my research.”

What a quaint 1970s point of view from this (otherwise) mostly modern Millennial. Get a job. Really? You want to trade your intellect, your scholarship, your creativity, your value-creating pattern recognition and insight for… for fixed wages? From a bureaucratic corporate employer (who btw like almost all bureaucratic employers is trying to reduce their wage cost)?

The very concept of “getting a job” for an employer, and “trading your time” for the security of “wages” (and benefits) is an exceedingly recent one—and has had a shorter life than anyone predicted.

The Big Idea of the Industrial Revolution was Division of Labor, right? The idea was we needed people to work at jobs—repetitively replicating their actions with an emphasis on consistent output, supervised, hierarchical, and with as little variability as possible. Creativity not encouraged. And through that boring, dull, and at times heavy, unsafe, and physically demanding work, these people swapped the freedom of the hunter-gatherer life (and its feast or famine) for the seeming security of a fixed wage.

That has always seemed a losing trade to me. Why would you give up your freedom of purpose, freedom of where you work, who you work with, or when you work—and allow the surplus capital from the value you create to accrue to others—for the supposed security of a fixed wage? Why would we be afraid to live by our wits?

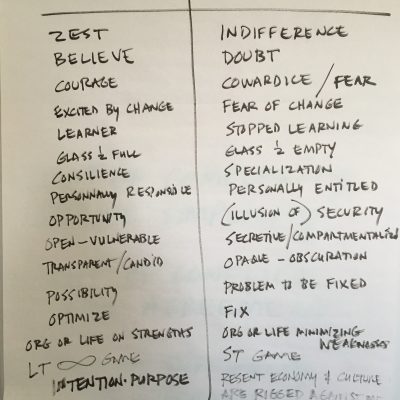

During the short duration of our careers so far, our world has undergone a power shift: from the wage economy where we barter our time for an hourly or daily wage, to the entrepreneurial economy where first we bring value, and then negotiate our compensation as a slice of the value we bring.

In the last 150 years (the short period of the Industrial Revolution), we could be forgiven if we felt like the game was rigged against individual contribution, meaning, and success. The large bureaucratic organizations had most of the resources. Formerly, they had an asymmetry of information, execution, access to media, access to politicians, access to capital.

Today however, the entrepreneurial force multiplier made up of the continually increasing speed of computing, the dramatically declining cost of computing, and ubiquity of on-line access has utterly leveled the playing field. Today what the rules-based bureaucratic bog has is a commodity (has turned into baggage, reducing their agility and ability to attract and retain talent). What the entrepreneurial world has is what is scarce and valuable. Taking the long long term view, this is an extraordinary time of entrepreneurial opportunity in human history. It has never been this good, and who knows if it ever will again.

All homo sapiens are entrepreneurs. When we were in caves, we were making tools for our own use. For roughly 200,000 years as hunter-gatherers, we learned to track and kill for our meals. For roughly 12,000 years of the agricultural age, we raised crops (and bartered our crops for those we didn’t raise). Except in the last 150 years, we have always been Entrepreneur Owner-Managers. Craftspeople. Merchants. Artisans. Trades. We worked at home or at our forge, river, or common. We worked with whom we chose. We worked whatever hours we needed to stay warm, stay fed, fuel our striving for life purpose and meaning. The most productive of us worked on tasks that largely leveraged our superior skill or unique ability.

Then with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, for 150 short years we suppressed our creativity and innovation. Hell, who knows, maybe we had to. In order to achieve the productivity from division of labor, we had to specialize, sometimes to mundane, boring, repetitive, dangerous tasks in a rules-based culture. Over and over. During the same hours. At the same factory. So for a few generations, the way it went was we entered the workforce, had one year’s experience repeated forty times (not authentically 40 years of experience), and “retired,” exhausted, to try to work on our own sense of meaning and purpose. Not merely our employers purpose, to whom we had been selling our time by the hour.

Today, if you are only thinking about “a job,” the mental model you are referring to is of a world that has ceased to exist (and only existed for 150 years or so in total). [As homo sapiens, we do have a quaint but unproductive characteristic in that we frequently look at recent experience or recent history and tend to project it linearly and infinitely into the future. Behavioral economists call that a form of status quo bias. But history is more than 150 years.]

Have you noticed another curious fact? In the last 35 years, all the epic human stories are entrepreneur stories. There are no more hero stories of gloried military commanders, no stories about selfless statesmanship or splendid political leadership as there may have been 100 years ago. Why? All of the improvements in our quality of life have come from the private entrepreneur sector, not the public one. I don’t say I love every entrepreneurial innovation in our culture. But if you think any innovation or creativity to improve the quality of your life has come out of the public sector in the past 35 years, then you haven’t been paying attention.

Let’s reframe the initial job question. Instead of asking, “How can I get a job,” why wouldn’t we ask, “How can I use my unflagging curiosity, unique superior skills, and passion and persistence in my chosen domain to bring measurable tangible value to others? Then, how can I negotiate to get paid a slice of that?”

Machines continue to liberate humans from formerly drudge work and simultaneously increase economic surplus. This is going to continue to drive upward mobility. (And to be sure, will permit downward mobility as well). As more and more repetitive tedious tasks get routinely taken by computers or computer controlled devices (learning machines) which do that work better, that sets us free to use our unique human-ness—our “consciousness” to bring value in ways that machines will be forever unable to do.

Entrepreneurial work is not a self-centered act or a bid for attention on the part of the individual. It has proven to be a gift to the world and every single one of us in it. Entrepreneurial effort doesn’t give. It gives back from your investment of courage, persistence, and passion. You never make progress as an individual or as an organization by choosing security or comfort over innovation or discomfort.

Don’t merely “get a job” and cheat us out of your entrepreneurial contribution. Have courage. Live by your wits. Give us everything you’ve got.

References and Further Reading:

Brand, Stewart. The Clock of the Long Now: Time and Responsibility. New York: Perseus, 1999. Print.

C., Lockard Brett, and Michael Wolf. “Monthly Labor Review: Index to Volume 128 January 2005 through December 2005.” Monthly Labor Review 128.12 (2012): n. pag. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Jan. 2012. Web. 12 Apr. 2016.

Eagleman, David. Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain. New York: Vintage, 2012. Print.

Evans, Person. “We Should Be Worried about Job Atomization,.” TechCrunch. AOL Inc., 16 Apr. 2016. Web. 18 Apr. 2016.

Grant, Adam. Originals. New York: Viking, 2016. Print.

Hirschman, Albert O. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1970. Print.

McCloskey, Deirdre N. Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World. Vol. 3. Chicago: U of Chicago, 2015. Print.

Russell, Bertrand. The Conquest of Happiness. Oxford: Infinite Ideas, 2009. Print.